excerpt from Pastimes: The Beginnings of Pro Sports in Uplantica by Johan Tuwaa, 1998

Coming off its first season, the UPFF (Uplantic Professional Football Federation) and its team owners were cautiously optimistic. The Lydon family hostage crisis derailed Crystalline Casting’s coverage of the league through its inaugural season, but fans still flocked to stadiums, with millions tuning their radios to the 1933 Uplantic Bowl on New Year’s Day. The Uplantic Bowl broadcast was, at the time, the most widely heard live broadcast in radio history. As the league prepared for its final events of the season, the awards banquet and the all-star game, Catherine Pennington met with Crystalline Casting executives to work out a coverage deal for the 1933-34 season.

The future was looking bright for the UPFF until a troubling rumor hit front offices on Wednesday morning, January 4.

Jim De La Costa, the owner of the Green Rock Warriors, was resting at home in Green Rock when he received a surprise phone call. “I got a call from [Delle Chaparrals owner] Joe [Horn] at about fifteen after nine, and I said ‘Joe, don’t you know the season just ended? Take a day off!’ Joe didn’t laugh. He asked me if I’d heard from the office. I said ‘no’ and Joe said ‘They cheated, Jimmy! They really did it!'” De La Costa and Horn spoke for a few minutes, and when they hung up, De La Costa’s telephone rang again immediately. The Warriors office had received the same letter that prompted Joe Horn’s initial call to De La Costa’s home. “I remember telling my wife Jan, ‘I guess I’m going to work today.'”

The letter came from an unknown source, delivered to every team’s executive office. To this day, the sender has never been revealed. In the letter, the author lays out evidence of collusion between the Northsouth Athletics organization and the league, including evidence of league co-founder Giles Lydon having wielded his influence to gather strategic information on behalf of the Athletics.

The allegations against Giles Lydon were shocking, especially with Lydon having become something of a national darling across Uplantica after his son’s family was rescued from a terrorist group in September after a weeks-long ordeal.

Jim De La Costa remembers: “I didn’t believe it. I couldn’t believe it. But then I read the letter again. It laid it all out. It was all there, it all made sense.”

An investigation confirmed weeks later that Giles Lydon had employed a spy network throughout the league, personally loyal to him. Lydon reportedly provided confidential medical reports, internal team memos, and even photos of opposing team practices to Athletics general manager Juan Stepp.

Juan Stepp initially denied the accusations in a short statement delivered to the press on January 6, but that afternoon Giles Lydon called a press conference. In it, he confessed to every accusation in the mysterious letter. Aside from the dishonor of having cheated, many of the accusations amounted to crimes of espionage that would carry serious civil consequences. “I did it for money. I’ve lost my way. I didn’t…I wouldn’t…” Lydon kept a straight face, but did not finish his sentence. He did not take any questions and seemed to stare off into space before wandering away from the microphone.

UPFF co-founder Catherine Pennington was perhaps the most shocked by her longtime friend and collaborator’s behavior. She resigned as UPFF commissioner shortly after learning of Lydon’s confession. Years later, in a rare interview in 1946, she said, “The world dropped out from under me. Giles was my best friend. We had built so much together for so long. The man I knew was someone else. I don’t think I’ve ever been the same. This world, this life, just isn’t what I thought it was.”

For a time, Pennington maintained that Lydon had to have been somehow threatened or influenced by the terrorist group that abducted his son, daughter-in-law, and grandchildren. However, an investigation made it clear that Lydon was involved in illicit and morally questionable activity long before and independent of the abduction incident. No link has ever been made between the abduction and Giles Lydon’s crimes. Catherine Pennington has never been accused of any crime or any knowledge of Lydon’s crimes.

The UPFF, which had a positive outlook on the morning of January 4, was in shambles by the evening of January 6. With much of the league’s leadership having already stepped down in the hours since Lydon’s public confession, and most of the remaining brass about to be under investigation for crimes tied to Lydon, the league shut down the upcoming weekend of awards and all-stars. The Northsouth Athletics organization disbanded almost immediately, and by the next week, the remaining owners unanimously voted to dissolve the UPFF. Just like that, the league that so many people had worked so hard to create was gone.

In the wake of the UPFF’s dissolution, team owners met with various investor groups, but the owners could not agree on a plan to move forward. Of the nine remaining UPFF teams, three were reportedly close to folding by mid-April. And, without a future season on the schedule by the end of the month, contract clauses across the league would free all players from future service, but guarantee severance pay that would bankrupt nearly every former UPFF organization.

The owners agreed to hear one more league pitch on April 20, despite four of five owners voting ‘no.’ The pitch came from six team owners who had already been planning a league to rival the UPFF. The former UPFF owners were impressed, and the fifteen organizations entered into a pact to form a new league to begin play in the fall of that year.

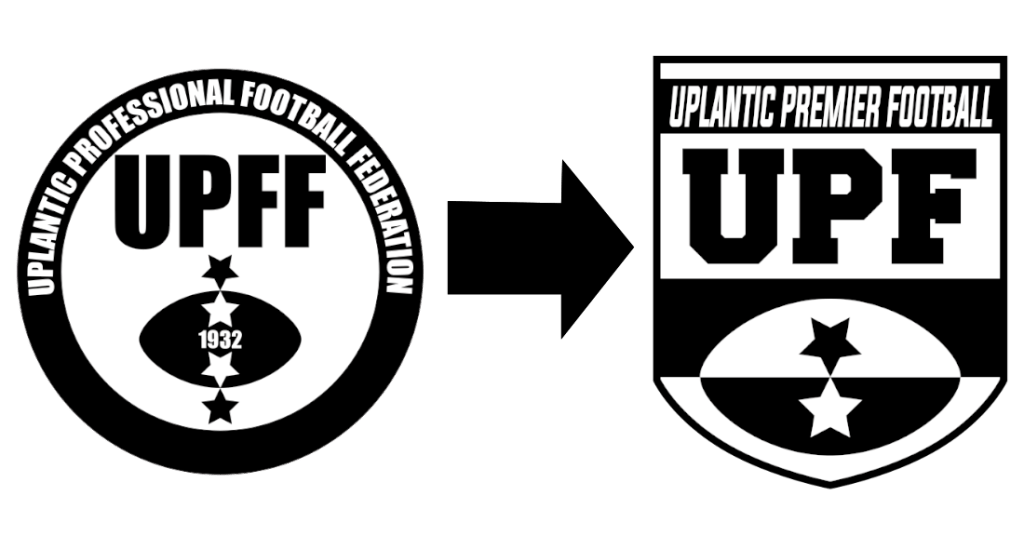

The owners offered the commissioner position to Catherine Pennington, but she turned it down. The athletic director of Duchess University, Madelaine Wilkins, was chosen as commissioner, and she introduced the new league, dubbed “Uplantic Premier Footbhall (UPF),” to the press for the first time on May 10, 1933. “We’re looking ahead to the future, and we’re preserving the integrity of the game of football in the face of a treacherous world.”

Every member of the Northsouth Athletics office and coaching staff was banned for life from the UPF. The Athletics players were allowed to enter the new league as free agents, as no link was found between the team’s cheating staff and individual players. The UPF assigned “parity officers” to oversee each team’s operations, to ensure fair play. Opponents of this policy protested that the league’s own agents could be turned into a new spy network like Giles Lydon’s, but the majority of owners voted in favor of the new league’s security measures.

The UPF added a brand new team in Northsouth before the league began play in the fall of 1933, with a total of sixteen teams. With the blessing of Catherine Pennington, the UPF retained the “Uplantic Bowl” moniker and continued to use the Pennington Cup as its championship trophy.